Contents

Introduction 1

Anil Hira and Maureen Benson-Rea

Threads of Despair: An Argument for the Public Option in Garment Governance 29

Anil Hira

The Legacy of Rana Plaza: Improving Labour and

Social Standards in Bangladesh’s Apparel Industry 81

Mustafizur Rahman and Khondaker Golam Moazzem

A Governance Deficit in the Apparel Industry

in Bangladesh: Solutions to the Impasse? 111

Mohammad Tarikul Islam, Amira Khattak, and Christina Stringer

Anti-consumption and Governance in the Global

Fashion Industry: Transparency is Key 147

Michael S.W. Lee, Miriam Seifert, and Helene Cherrier

Index 175

List of Figures

Fig. 1 (a–c) Export composition of Bangladesh, 1981–2007 4

Fig. 2 Growth of clothing exports from Bangladesh 5

Fig. 3 (a–d) Top sources of US textile and apparel imports,

1989 and 2013 7

Fig. 4 German imports from Bangladesh, 1988–2013, euros 8

Fig. 1 Economics perspective 36

Fig. 2 ILO/labour rights perspective 39

Fig. 3 Global value chains/corporate codes perspective 41

Fig. 4 Hira governance model 70

Fig. 1 Fragmented value chain with limited focus on compliance

costs through different means 89

Fig. 2 Participation of different market players in monitoring

labour and social standards during pre-Rana Plaza period 93

Fig. 3 Participation of different market players in monitoring

labour and social standards during the post-Rana

Plaza period 103

Fig. 1 Interrelated governance model 137

Fig. 1 Triad of transparency 165

List of Tables

Table 1 Private monitoring initiatives 98

Table 2 Progress of remediation in Accord-inspected factories 99

Table 3 Progress of remediation in Alliance-inspected factories 100

Table 1 Growth of the Bangladesh apparel industry from 1983 to 2014 119

Table 2 Top apparel exporting countries 120

Table 3 A snapshot of recent disasters in Bangladeshi factories 122

Table 4 Governance institutions in the apparel industry in Bangladesh 132

Introduction

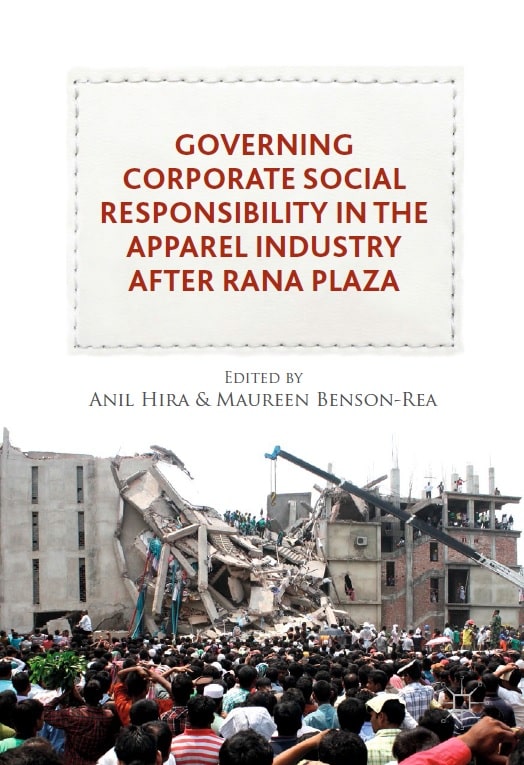

Over several decades, stories about workers in developing countries who suffer from disastrous working conditions while making consumer goods have become part of the economic landscape. The means of resolving such issues seem tantalisingly simple. A study in 2011, for example, suggested that a mere increase of 2–6% in the final retail price could finance a 100% increase in production worker wages in the garment industry (Heintz 2011, 269). As recently as 2012, a series of reports by the New York Times about FoxConn, the premier electronics components manufacturer in the world, including for Apple, revealed a rash of worker suicides committed in protest against conditions in Chinese factories. Apple promised to set things straight, but serious doubts remain. The clothing factory collapse in Rana Plaza (RP) in Bangladesh on April 24, 2013 received worldwide attention. The latest disaster epitomised a continuing lack of basic worker safety standards, and the inability of (largely) Western clothing companies to meet their pledges, stated many times before, that the situation had been rectified. Meanwhile, a series of strikes by Cambodian textile workers pushed for minimal wage increases in 2014, but the government warned that work would be lost to other countries (Murphy 2014). Cambodia set the 2016 minimum wage for garment workers at $140 per month, a $12 increase from the previous rate of $128, but still below union demands for $160. Many of the workers in the apparel industry are women with few career options, giving rise to the potential for ongoing exploitation.

In this volume, we evaluate the post-RP agreements by multinational companies to improve labour standards in Bangladesh. The agreements offer different sets of governance arrangements through cooperative consortia and auditing of supply chains on a deeper level than has ever been tried before. Once again, companies promise “never again”. The February 2, 2016 factory fire of the Matrix Sweater Factory in Gazipur involving clothing being made for H&M and JC Penney belies such bold statements and forces us to re-examine the issue for how the new arrangements can be improved or what new governance arrangements need to be considered. In fact, shortcomings in the factory had been flagged by one of the new consortia, the Alliance (as discussed later in this chapter), but remediation was never undertaken (Stangler 2016).

This volume sets out to examine the new arrangements in regard to both their promise of reforming labour standards and their implications for corporate strategy. In setting and pursuing their strategies, firms take positions in markets and value chains and must understand the institutions and contexts which shape their strategic options, especially in emerging markets such as Bangladesh (Rottig 2016). One of the most pressing sets of issues in the international environment for business is managing the quality and ethical standards of supply chain partners. Compliance involves costs; even if difficult to calculate, different governance arrangements for compliance will imply different cost levels and structures imposed on different actors. This is especially challenging when firms based in advanced economy locations must evaluate suppliers and partners in developing countries, which may be characterised by institutional voids, where market arrangements are weak or absent altogether (Amaeshi et al. 2008), but with which firms from developed economies must nonetheless engage. Institutional voids in the area of labour standards are particularly challenging since it is unclear whether multinational corporations (MNCs) are (or should be) able to bridge institutional voids with ‘informal social institutions and social contracts’ (Rottig 2016, 5).

The issue of responsibility is an unclear one, but clearly the multinationals bear some. In April 2015, a $2 billion class action lawsuit was filed on behalf of the RP victims, alleging that the defendants were well aware of the conditions and failed to carry out proper inspections and audits. It is important to point out that the RP accords create new approaches for a variety of issues, ranging from worker safety to unionisation. We take a broad approach towards examining if the strategic innovations in governance represented by RP, particularly the construction of consortia of Western companies, constitute a more promising way to achieve improvements across those related issues. Given the weak institutional structure for maintaining social compliance in developing countries, the need to develop workable models of governance of the apparel sector cannot be over emphasised. Our overall question, then, is whether the post-RP arrangements will help to provide an effective new model for the governance of labour standards.