by Dana Thomas

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

PART ONE

ONE: An Industry Is Born

TWO: Group Mentality

THREE: Going Global

PART TWO

FOUR: Stars Get in Your Eyes

FIVE: The Sweet Smell of Success

SIX: It’s in the Bag

SEVEN: The Needle and the Damage Done

PART THREE

EIGHT: Going Mass

NINE: Faux Amis

TEN: What Now?

ELEVEN: New Luxury

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

NOTES

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

DOWN THE DUSTY ROADS of Xi’an the motor scooters zoom, weaving around potholes and rickety bicycles, bip-bip-bipping their horns as they circle the city’s sixteenth-century bell tower. Xi’an, pronounced Shee-ahn, is one of China’s oldest cities, settled by humans since prehistoric times. From 221 BC to AD 907, Xi’an served on and off as the capital of the vast Chinese empire. The famed Silk Road, the trade route that linked the Far East to Europe, started there in the second century BC and turned the city, then known as Chang’an, into a throbbing metropolis of nearly two million and an epicenter for culture and politics. Painting, poetry, dance, and music thrived in Xi’an, and l’art de vivre—the refined art of living—was an essential component of everyday existence. Xi’an was so beautiful—with its elaborate Buddhist temples, mosques, bustling souks, and eighth-century walled imperial city—that Japan’s emperors used it as a model for their imperial capitals of Kyoto and Nara. It was said that Xi’an was as cosmopolitan and influential as Baghdad, Constantinople, and Rome. Many considered it the greatest city in the world.

It is hard to imagine today. With a population of 8 million, Xi’an is a small city by Chinese standards, compared to Shanghai (17.8 million), Beijing (15 million), and Chongqing (12 million). Unlike Beijing and Shanghai, which, thanks to China’s market reforms, have become vibrant international capitals, Xi’an suffers from the blight of communism. The people, many dressed in faded Mao suits, seem downtrodden. Nothing has been painted in decades; scooters are held together with string, tape, and hope; and everything is covered in dust and soot. The new wealth of China has not trickled down to Xi’an—at least not yet. It has some local industry —cotton textiles, chemicals, and high tech—but its most important business is tourism. Half an hour away by car is the site of the Terracotta Warriors, the eight thousand life-size soldiers and horses that were buried in the tomb of Shi Huang Ti (259–210 BC), the first emperor of Qin (or China), for more than two thousand years and discovered in 1974 by a farmer digging a well. Each year, more than twenty million tourists—primarily Chinese—travel to Xi’an to see the warriors, making the site one of the country’s most popular tourist destinations.

In April 2004, my husband and I traveled to China for the first time. I was there to cover the opening of Giorgio Armani’s new retail complex on the Bund, the waterfront promenade in Shanghai. Afterward, we went to Xi’an to see the Terracotta Warriors. We arrived in the spanking-new airport on the outskirts of the city and took a beat-up cab down the factory-lined highway and tenement-lined streets to the historic center. We checked in to the Hyatt Regency, one of the two “Western” business hotels at the time, and as we stood there in the polished marble lobby and plant-filled atrium, I remembered that the word Xi’an means “western peace”: the Hyatt seemed transplanted directly from any American urban center.

On the way to breakfast the first morning, we came across a couple of Chinese vendors selling clothes in a small conference room on the mezzanine. Not just any clothes: spread out across a half dozen folding tables were Gucci and Versace men’s loafers, Givenchy men’s shirts and socks, Versace sweaters, Calvin Klein underwear, Gucci sweaters with tags in them that read “Designed in Italy,” and hanging on a garment rack in the corner, a couple of Burberry men’s trench coats. Some of the items were obviously fake—several of the Versace shirts were labeled “Verla” in the same font—and I knew that Chinese factories turned out counterfeit goods of every sort. But some looked suspiciously authentic. I picked up the Gucci loafers. They were made of good-quality leather, well stitched, with a slight mod design to them, just like the shoes you find in Gucci stores on Rodeo Drive or Madison Avenue. My husband tried on one of the alleged Burberry trenches. It, too, was well made and with all the Burberry details just right. We asked the price. No one in the room spoke English, but a thin twentysomething Chinese girl pulled out a calculator and tapped out the price: $120. The regular retail price for a Burberry men’s classic trench is $850. My husband said he’d think about it. We stopped by the concierge desk to ask about the provenance of the goods. Most were legitimate, the concierge told us, and had slight defects, were from an overrun, or simply didn’t fit into the shipping container.

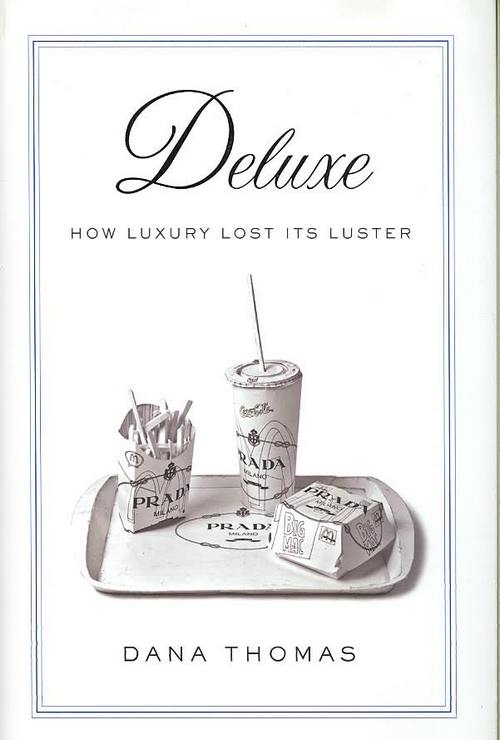

THE LUXURY GOODS INDUSTRY, as it is known today, is a $157 billion business that produces and sells clothes, leather goods, shoes, silk scarves and neckties, watches, jewelry, perfume, and cosmetics that convey status and a pampered life—a luxurious life. Thirty-five major brands control 60 percent of the business, and dozens of smaller companies account for the rest. Several, including Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Prada, Giorgio Armani, Hermès, and Chanel, have annual revenues in excess of $1 billion. Most luxury goods companies that we know today were started a century or more ago as simple one-man or one-woman shops that sold beautiful handcrafted pieces. Today those companies still carry the founders’ names but are, for the most part, owned and run by tycoons who in the last two decades have turned them into multibillion-dollar corporations and omnipresent global brands. They cluster their stores on main city avenues, in airports, in outlet malls. Their advertisements fill magazines and blanket billboards. Their primary customers are upper-income women between thirty and fifty years old. In Asia, the customer base veers younger, starting at twenty-five.