Contents

List of Illustrations vii

Acknowledgements xi

Notes on Contributors xiii

Introduction: Islamic Fashion and Anti-fashion: New Perspectives from Europe and North America 1

Annelies Moors and Emma Tarlo

SECTION I: LOCATION AND THE DYNAMICS OF ENCOUNTER 1.

Burqinis, Bikinis and Bodies: Encounters in Public Pools in Italy and Sweden 33

Pia Karlsson Minganti

2. Covering Up on the Prairies: Perceptions of Muslim Identity, Multiculturalism and Security in Canada 55

A. Brenda Anderson and F. Volker Greifenhagen

3. Landscapes of Attraction and Rejection: South Asian Aesthetics in Islamic Fashion in London 73

Emma Tarlo

4. Perspectives on Muslim Dress in Poland: A Tatar View 93

Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowska and Michał Łyszczarz

SECTION II: HISTORIES, HERITAGE AND NARRATIONS OF ISLAMIC FASHION

5. Şule Yüksel Şenler: An Early Style Icon of Urban Islamic Fashion in Turkey 107

Rustem Ertug Altinay

6. The Genealogy of the Turkish Pardösü in the Netherlands 123

R. Arzu Ünal

7. Closet Tales from a Turkish Cultural Center in the ‘Petro Metro’, Houston, Texas 142

Maria Curtis

SECTION III: MARKETS FOR ISLAMIC FASHION

8. Transnational Networks of Veiling-fashion between Turkey and Western Europe 157

Banu Gökarıksel and Anna Secor

9. Made in France: Islamic Fashion Companies on Display 168

Leila Karin Österlind

10. Hijab on the Shop Floor: Muslims in Fashion Retail in Britain 181

Reina Lewis

SECTION IV: ISLAMIC FASHION IN THE MEDIA

11. ‘Fashion Is the Biggest Oxymoron in My Life’: Fashion Blogger, Designer and Cover Girl Zinah Nur

Sharif in Conversation with Emma Tarlo 201

12. Mediating Islamic Looks 209

Degla Salim

13. Miss Headscarf: Islamic Fashion and the Danish Media 225

Connie Carøe Christiansen

SECTION V: DYNAMICS OF FASHION AND ANTI-FASHION

14. Fashion and Its Discontents: The Aesthetics of Covering in the Netherlands 241

Annelies Moors

15. The Clothing Dilemmas of Transylvanian Muslim Converts 260

Daniela Stoica

16. ‘I Love My Prophet’: Religious Taste, Consumption and Distinction in Berlin 272

Synnøve Bendixsen

Index 291

Introduction: Islamic Fashion and Anti-fashion: New Perspectives from Europe and North America

Annelies Moors and Emma Tarlo

The past three decades have seen the growth and spread of debates about the visible presence of Islamic dress in the streets of Europe and North America. These debates, which have accelerated and intensified after 9/11, focus on the apparent rights and wrongs of headscarves and face veils, on whether their wearing is forced or chosen and to what extent they might indicate the spread of Islamic fundamentalism or pose security concerns. Such dress practices are also perceived as a threat to multiculturalism and to Euro-American norms and values which are often spoken of as if they are fixed and shared. Such arguments have been used to support bans and restrictions on Islamic dress practices in the name of modernity, secularism or women’s emancipation. What is curious about these debates is not only the way in which they have become so entrenched but also how out of tune they are with actual developments in Muslim dress practices which have, over the past decade, been undergoing rapid transformation. They ignore, for example, the development and proliferation of what has become known, both in Muslim circles and beyond, as Islamic fashion and how the emergence of such a phenomenon does not so much signal Muslim alienation from European and American cultural norms as complex forms of critical and creative engagement with them. This book grows then out of awareness of the discrepancy between public discourses about Muslim dress and actual developments in Islamic fashion in the streets of Europe and America, pointing to the need for greater understanding and more nuanced interpretation. Taking critical distance from the popular assumption that fashion is an exclusively Western or secular phenomenon, it points to the complex convergence of ethical and aesthetic concerns expressed through new forms of Islamic fashion whilst simultaneously highlighting the ambivalence some Muslims feel towards such developments. It also suggests that just as Islamic fashion engages with and contributes towards mainstream fashion in various ways, so

Muslim critiques of fashion often share much in common with critiques from secular and feminist sources.

The research on which this book is based was conducted in a variety of cities across Europe and America, enabling us to gain perspective both on the diversity of Islamic dress practices in different locations and on different regional responses to these. The aim was not to gain statistical representativity but to elucidate how Muslim women in different locations relate to Islam, dress and fashion through a series of qualitative case studies. Although the range of countries and cities covered is far from exhaustive, it does provide a basis for identifying common themes as well as the specificities of particular sites. Whilst such comparative observations mediate against simplistic ideas of a single Muslim culture, they also highlight the extent to which so-called Euro-American values and norms are far from clear cut and that what counts as European is based on a very particular Western and Northern European experience. By bringing the experiences and clothing preferences of Muslims in Eastern Europe into the equation, including Polish Tatars, Arab migrants and Romanian converts, we gain a sense of just how varied the European Muslim experience and forms of cultural expression are.

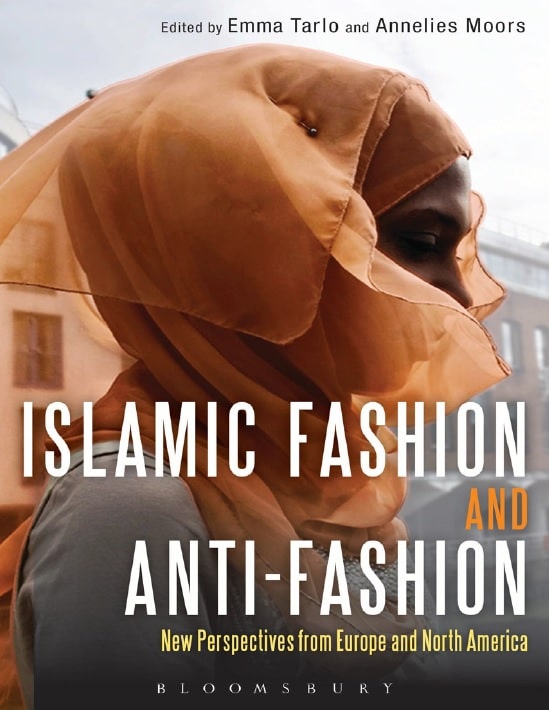

One lesson quickly learned by all the researchers who have contributed to this book is the impossibility of simply reading from appearances. To highlight this point we include an interview with Zinah, the young fashion blogger represented on the cover of this book whose attitudes towards fashion and matters of appearance only become accessible through dialogue. More generally, it has been through engaging with Muslim women concerning the motivations behind their dress that we have been able to gain insight into the complexity and sensitivity of the issues involved. For example, women wearing similar outfits may have very different motivations for doing so even within a specific location. In some cases, the adoption of a particular type of headscarf may be a first step towards starting to wear covered dress; in other cases, for those who used to wear more sober forms of covering in the past, the very same headscarf may be a step towards experimentation with more fashionable styles. Opinions also vary substantially concerning how much a woman ought to cover and to what extent covering can be considered a religious virtue. In addition, decisions about what to wear are made in relation to the attitudes and opinions of relevant others, whether family, peers in school, colleagues at work or even strangers, all of whom may express approval or disapproval of particular trends. They are also influenced by popular culture and political contexts, which may be more or less conducive to developments in Islamic fashion. In continuity with our earlier research (Tarlo and Moors 2007; Moors 2009a; Tarlo 2010b, 2013b), we have found it particularly important to consider dress biographies and the contexts in which they operate, which include concerns about religion, ethnicity, class, generation and fashion. At the same time, we have been struck by the variety of styles worn, not only between women in different regional settings but also amongst women living in the same locations.

In this introduction, we begin by discussing some of the key debates raised by the study of Islamic fashion in Europe and America, addressing the relation between dress and religion, the turn towards materiality in religious studies, women’s religious agency and the importance of considering style. We contextualize the emergence of Islamic fashion in Europe and America by reference to the spread of a global Islamic revival and the increased emphasis placed on reflexive forms of Islam. We review how clothing practices have transformed in Muslim majority countries from the 1970s onwards and how these changes relate to recent developments in Islamic fashion in Europe and America. At the same time, we engage with fashion theory, suggesting how Islamic fashion enables us to question many of the assumptions embedded within the world of fashion and fashion scholarship. In particular, we draw attention to the relationship between ethics and aesthetics in Islamic fashion and anti-fashion discourses and practices. We also point to the significance of location and how the Muslim presence in different European and American contexts follows different historical trajectories and engages with different forms of secular governance which shape clothing possibilities for Muslims in particular ways. We end by drawing out some of the key themes that have emerged through comparing Muslim experiences and fashions in diverse locations ranging from a small city in the Canadian prairies to large European cities, including London, Paris, Berlin, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Cluj and Amsterdam. Our key contention is that through their visual material and bodily presence young women who wear Islamic fashion disrupt and challenge public stereotypes about Islam, women, social integration and the veil even if their voices are often drowned out in political and legal debates on these issues.